In July, 2014 I visited Denali National Park, Alaska, as one of the artists-in-residence. It was an amazing trip. I am so grateful to all the park staff and the AIR program selection committee who made it possible.

(From "18 Meditations from Denali" by Angela Morales, copyright Denali National Park)

July, 2015

1.

Northbound to Alaska, the plane rises above the smog-line of Los Angeles, gliding through a cocktail of metallic particles, methane, and carbon monoxide. I’ve been granted a ten-day respite from asphalt and freeways and bumper-to-bumper traffic, and from up here, so much concrete punctuated by patches of greenery and turquoise swimming pools seems etched onto a massive grid, like the motherboard of some gigantic computer. An average of 2, 750 people live packed into each square kilometer of L.A., but even down there, in all that chaos, live raccoons, skunks, coyotes, and even mountain lions, taking space wherever they can get it—in sewers, in crawlspaces, in pockets of the foothills. Leaning back at ten-thousand feet, I close my eyes and try not to think about our limited water supply, children’s respiratory problems, and whether the animals will survive our three-year drought.

Two thousand miles later, I catch my first breathtaking glimpse of the Gulf of Alaska and the land that stretches beyond it. Vast glacier-rivers cut deep into ice-glazed earth, all this surrounded by verdant slopes and shore. So much geologic momentum, as the edges of the continent shift and break apart into inlets and islets. Permafrost contrasts with basalt and volcanic ash, evidence of the earth’s breathing and exhaling, burning and freezing. I’ve arrived at this state with a coastline longer than all other states combined; this land, stretching 2,261 miles wide—a distance greater than the distance I’ve traveled to get here; this place with names like Arctic Village and Salmon River, or historically descriptive names like Mary’s Igloo, Buffalo Soapstone, Unalaska, Women’s Bay, or Kalifornsky, and towns with native names that feel nice on the tongue like Chignik, Kipnuk, Yakataga, and Savoonga.

July, 2015

1.

Northbound to Alaska, the plane rises above the smog-line of Los Angeles, gliding through a cocktail of metallic particles, methane, and carbon monoxide. I’ve been granted a ten-day respite from asphalt and freeways and bumper-to-bumper traffic, and from up here, so much concrete punctuated by patches of greenery and turquoise swimming pools seems etched onto a massive grid, like the motherboard of some gigantic computer. An average of 2, 750 people live packed into each square kilometer of L.A., but even down there, in all that chaos, live raccoons, skunks, coyotes, and even mountain lions, taking space wherever they can get it—in sewers, in crawlspaces, in pockets of the foothills. Leaning back at ten-thousand feet, I close my eyes and try not to think about our limited water supply, children’s respiratory problems, and whether the animals will survive our three-year drought.

Two thousand miles later, I catch my first breathtaking glimpse of the Gulf of Alaska and the land that stretches beyond it. Vast glacier-rivers cut deep into ice-glazed earth, all this surrounded by verdant slopes and shore. So much geologic momentum, as the edges of the continent shift and break apart into inlets and islets. Permafrost contrasts with basalt and volcanic ash, evidence of the earth’s breathing and exhaling, burning and freezing. I’ve arrived at this state with a coastline longer than all other states combined; this land, stretching 2,261 miles wide—a distance greater than the distance I’ve traveled to get here; this place with names like Arctic Village and Salmon River, or historically descriptive names like Mary’s Igloo, Buffalo Soapstone, Unalaska, Women’s Bay, or Kalifornsky, and towns with native names that feel nice on the tongue like Chignik, Kipnuk, Yakataga, and Savoonga.

2.

In Anchorage just before midnight, the sun lingers below the horizon as ravens and seagulls behave like its midday—circling and chattering, no mind to the time. After picking up the rental car—an alarmingly red Chevy Cruze—I find a big all-night grocery store where I can stock up on food for the days ahead. In the parking lot of the Fred Meyer, I gawk at the show of birds as they flap their wings low overhead. Don’t they realize that birds should be asleep by now, heads tucked under their wings? But should they be asleep? Feeling wide awake myself, I check items off my list and throw them into the cart, not sure if I’ll need the jumbo-sized can of pepper spray. Really? I can’t imagine that I’ll really need it. The only bears I’ve encountered are black bears that sometimes wander down from our San Gabriel Mountains searching for water and pawing through pizza boxes left in dumpsters. Either people chase them away with golf clubs or give them cute names like “Meatball” and then, feeling sorry for them, leave food out on purpose. Inevitably, an officer from the Department of Fish and Wildlife comes out, shoots the animal with a tranquilizer dart, and then drives “Meatball” back up to the forest. Anyway, I decide to hold off on the pepper spray until I get to Denali. We’ll just have to see about that.

After my late night shopping trip, I meet up with my best friend Dana who arrives on the red-eye from Sacramento. Dana and I first met when we were assigned to be college roommates in the dorms at U.C. Davis. Ever since then, she’s been a part of the family. We’ve traveled together to China, the Middle East, North Africa, Europe, and Mexico, and now she’s agreed to meet me in Alaska—a place neither one of us has ever been. I’m super excited to see my pal, looking forward to another adventure together. We load Dana’s gear into the Cruze and head back to the hotel for a couple hours of sleep before heading north to Denali and into the wild.

In Anchorage just before midnight, the sun lingers below the horizon as ravens and seagulls behave like its midday—circling and chattering, no mind to the time. After picking up the rental car—an alarmingly red Chevy Cruze—I find a big all-night grocery store where I can stock up on food for the days ahead. In the parking lot of the Fred Meyer, I gawk at the show of birds as they flap their wings low overhead. Don’t they realize that birds should be asleep by now, heads tucked under their wings? But should they be asleep? Feeling wide awake myself, I check items off my list and throw them into the cart, not sure if I’ll need the jumbo-sized can of pepper spray. Really? I can’t imagine that I’ll really need it. The only bears I’ve encountered are black bears that sometimes wander down from our San Gabriel Mountains searching for water and pawing through pizza boxes left in dumpsters. Either people chase them away with golf clubs or give them cute names like “Meatball” and then, feeling sorry for them, leave food out on purpose. Inevitably, an officer from the Department of Fish and Wildlife comes out, shoots the animal with a tranquilizer dart, and then drives “Meatball” back up to the forest. Anyway, I decide to hold off on the pepper spray until I get to Denali. We’ll just have to see about that.

After my late night shopping trip, I meet up with my best friend Dana who arrives on the red-eye from Sacramento. Dana and I first met when we were assigned to be college roommates in the dorms at U.C. Davis. Ever since then, she’s been a part of the family. We’ve traveled together to China, the Middle East, North Africa, Europe, and Mexico, and now she’s agreed to meet me in Alaska—a place neither one of us has ever been. I’m super excited to see my pal, looking forward to another adventure together. We load Dana’s gear into the Cruze and head back to the hotel for a couple hours of sleep before heading north to Denali and into the wild.

3.

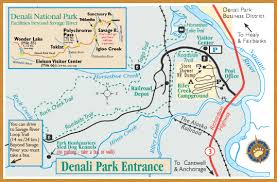

Memory: I’m ten years old and my mother is driving us to Yosemite National Park. She’s tossed some sleeping bags into the back of our two-toned Dodge Van and we’re heading north on Interstate 99 to Fresno where we veer East into the Sierras. It’s a six-hour drive from Los Angeles, or more like eight hours, if you count all the bathroom and snack stops required for five children plus a few cousins. We’re hot and cranky because we do not yet understand the payoff: a dip in the icy Merced River, our first dazzling view of the Milky Way, the snaky-hot embers of a campfire. I’ll never forget my first glimpse around that bend into Yosemite Valley—a mindboggling view of El Capitan and Half-Dome. The valley smelled of sugar pines and sedges, all of nature churned up at once—a perfume of decaying leaves and mushrooms, sap and granite dust. At that moment I knew: I belonged in the wilderness. Ever since I got my first taste of the wilderness, I’ve longed to see Alaska, especially, Denali. Now I’m holding the key to the East Fork Cabin, and the permit taped inside the car’s window gives us access to the park road beyond restricted fifteen-mile marker. We pass the checkpoint at the Savage River Station, sign our names on a clipboard, and then: We are in.

What unrolls before us takes our breath away. To grasp what I am seeing, my mind tries to make all kinds of connections. Is this what the earth looked like a million years ago? Is this what the land would have looked before the dinosaurs? Dwarfed forests of pines, aspen, birch, and balsam dot the horizon as the snow-covered Alaska Range rises up in the distance. The dirt road winds as far ahead as the eye can see, meandering into the tundra, where trees shrink away, and the ground is covered by a spongy mat of vegetation.

Then at mile 43, just before the bridge that leads to Polychrome Pass, we spot the roof of the cabin, barely visible from the road. Outside of the car, we take deep breaths as we look all around, and the first thing we notice is the silence. But then, we cock our ears and hear a whole muted symphony. Mosquitoes buzz. The creek gurgles. Wind rustles the leaves of the willows and the grasses. A pair of magpies swoops down to survey the newcomers.

Memory: I’m ten years old and my mother is driving us to Yosemite National Park. She’s tossed some sleeping bags into the back of our two-toned Dodge Van and we’re heading north on Interstate 99 to Fresno where we veer East into the Sierras. It’s a six-hour drive from Los Angeles, or more like eight hours, if you count all the bathroom and snack stops required for five children plus a few cousins. We’re hot and cranky because we do not yet understand the payoff: a dip in the icy Merced River, our first dazzling view of the Milky Way, the snaky-hot embers of a campfire. I’ll never forget my first glimpse around that bend into Yosemite Valley—a mindboggling view of El Capitan and Half-Dome. The valley smelled of sugar pines and sedges, all of nature churned up at once—a perfume of decaying leaves and mushrooms, sap and granite dust. At that moment I knew: I belonged in the wilderness. Ever since I got my first taste of the wilderness, I’ve longed to see Alaska, especially, Denali. Now I’m holding the key to the East Fork Cabin, and the permit taped inside the car’s window gives us access to the park road beyond restricted fifteen-mile marker. We pass the checkpoint at the Savage River Station, sign our names on a clipboard, and then: We are in.

What unrolls before us takes our breath away. To grasp what I am seeing, my mind tries to make all kinds of connections. Is this what the earth looked like a million years ago? Is this what the land would have looked before the dinosaurs? Dwarfed forests of pines, aspen, birch, and balsam dot the horizon as the snow-covered Alaska Range rises up in the distance. The dirt road winds as far ahead as the eye can see, meandering into the tundra, where trees shrink away, and the ground is covered by a spongy mat of vegetation.

Then at mile 43, just before the bridge that leads to Polychrome Pass, we spot the roof of the cabin, barely visible from the road. Outside of the car, we take deep breaths as we look all around, and the first thing we notice is the silence. But then, we cock our ears and hear a whole muted symphony. Mosquitoes buzz. The creek gurgles. Wind rustles the leaves of the willows and the grasses. A pair of magpies swoops down to survey the newcomers.

4.

The East Fork Cabin, built in 1929, has been slept in by hundreds of people—most notably, Adolph Murie who observed wolves and other wildlife and advised the park on how it should manage these animals to keep the numbers in balance. Rangers and park employees also use the cabin; a notebook on the kitchen table contains the names, dates, and often amusing stories of some such visitors—stories of lynx sightings, bear shenanigans, and an account of a wolf discovered on the cabin porch gnawing a broomstick and tossing it up in the air.

The cabin records its own history with thick, burnished layers of sealant and, inside, logs that have been cut away to reveal knots in the wood, as well as cracks, striations, and places when the rough cuts have left deep slashes or notches in the grain. The gaps are stuffed with hemp or burlap or some other fibers which make one feel the age of the cabin and remind me of how many hands have worked over the years to weatherproof the walls from rain, snow, and subzero temperatures. I imagine Adolph Murie writing at a desk surrounded by equipment, children, cameras, notebooks, an adopted wolf-pup. It’s easy, too, to imagine this place in winter, visited by travelers who ski in, often with teams of sled dogs. I shiver just thinking about the whorls of ice fog outside with Aurora Borealis dancing overhead, while inside, the furnace cranks out blankets of heat as travelers unload all that wet gear and warm their chilblained fingers and toes against the bright blue flame.

Now banana bread bakes in the oven, the citronella candle is burning, and I’m sitting on the porch all bundled up and drinking tea. It’s raining steadily but the sky looks brighter off in the distance against the mountains. Because of the vastness of this place, you can look across the sky and see different weather patterns—sunshine in the east, rain in the west, clouds to the north, snow way up high.

“Squeaky” the Arctic squirrel who lives under the porch, darts out from his burrow, stands on his (her?) hind legs and stares at me. He looks me up and down, as he probably does all the visitors. Then he scurries off into the bush to continue his daily business. I feel like I should be working as hard as Squeaky who chomps a blade of grass in fast motion—one-hundred miles per hour!—most likely taking advantage of all those daylight hours before retreating to a long sleep in his subterranean den. So far, I can’t do much but sit idly and let this place wash over me, let myself melt into it, which is harder than it sounds for this city person who’s used to being bossed around by clocks.

The East Fork Cabin, built in 1929, has been slept in by hundreds of people—most notably, Adolph Murie who observed wolves and other wildlife and advised the park on how it should manage these animals to keep the numbers in balance. Rangers and park employees also use the cabin; a notebook on the kitchen table contains the names, dates, and often amusing stories of some such visitors—stories of lynx sightings, bear shenanigans, and an account of a wolf discovered on the cabin porch gnawing a broomstick and tossing it up in the air.

The cabin records its own history with thick, burnished layers of sealant and, inside, logs that have been cut away to reveal knots in the wood, as well as cracks, striations, and places when the rough cuts have left deep slashes or notches in the grain. The gaps are stuffed with hemp or burlap or some other fibers which make one feel the age of the cabin and remind me of how many hands have worked over the years to weatherproof the walls from rain, snow, and subzero temperatures. I imagine Adolph Murie writing at a desk surrounded by equipment, children, cameras, notebooks, an adopted wolf-pup. It’s easy, too, to imagine this place in winter, visited by travelers who ski in, often with teams of sled dogs. I shiver just thinking about the whorls of ice fog outside with Aurora Borealis dancing overhead, while inside, the furnace cranks out blankets of heat as travelers unload all that wet gear and warm their chilblained fingers and toes against the bright blue flame.

Now banana bread bakes in the oven, the citronella candle is burning, and I’m sitting on the porch all bundled up and drinking tea. It’s raining steadily but the sky looks brighter off in the distance against the mountains. Because of the vastness of this place, you can look across the sky and see different weather patterns—sunshine in the east, rain in the west, clouds to the north, snow way up high.

“Squeaky” the Arctic squirrel who lives under the porch, darts out from his burrow, stands on his (her?) hind legs and stares at me. He looks me up and down, as he probably does all the visitors. Then he scurries off into the bush to continue his daily business. I feel like I should be working as hard as Squeaky who chomps a blade of grass in fast motion—one-hundred miles per hour!—most likely taking advantage of all those daylight hours before retreating to a long sleep in his subterranean den. So far, I can’t do much but sit idly and let this place wash over me, let myself melt into it, which is harder than it sounds for this city person who’s used to being bossed around by clocks.

5.

The East Fork River splits according to the will of the melting glaciers, braiding across the gravel in patterns that vary each day. The channels, from above, look like tentacles emerging from the rocks. This river bed, and the tundra, in general, is a wide-open place where animals can move freely but also an arena where one can be sniffed out, stalked, pounced, and eaten. If you’re a caribou, it’s like

walking across an enormous dinner plate. A female grizzly smells the ripe scent of a caribou calf and follows her nose. A wolf spies her grizzly cub and circles round the bears. We find a chaos of footprints in smooth mud—a perfect record of two or more animals engaging in a tango of predator/prey.

Claw marks and hoof prints encircle the other, leading me to wonder about unconscious sacrifice and whether animals understand the needs of other animals. A Japanese foliage spider, Chiracanthium japonicum, for example, allows her spiderlings to feast on her body thus giving her offspring the strength to spread themselves far and wide. Does a fox mother ever offer herself up to a predator to save her young, perhaps when benefits outweigh the loss? Do animals somehow calculate such actions?

We tend to assume that everything a wild animal does is controlled by pure instinct, by behaviors programmed deep within the DNA, but to what extent do animals make choices that will lead to their success or demise? Furthermore: Do animals understand (or sense) that they can be eaten at any time? Do they feel their own loss in the moments before their death, during the kill? I am an animal, after all, and I cannot fully grasp the fact that I, too, can be eaten right now as I sit in the middle of this wide gravel bar cradling my coffee mug to my cheek and scratching this pen across the paper.

The East Fork River splits according to the will of the melting glaciers, braiding across the gravel in patterns that vary each day. The channels, from above, look like tentacles emerging from the rocks. This river bed, and the tundra, in general, is a wide-open place where animals can move freely but also an arena where one can be sniffed out, stalked, pounced, and eaten. If you’re a caribou, it’s like

walking across an enormous dinner plate. A female grizzly smells the ripe scent of a caribou calf and follows her nose. A wolf spies her grizzly cub and circles round the bears. We find a chaos of footprints in smooth mud—a perfect record of two or more animals engaging in a tango of predator/prey.

Claw marks and hoof prints encircle the other, leading me to wonder about unconscious sacrifice and whether animals understand the needs of other animals. A Japanese foliage spider, Chiracanthium japonicum, for example, allows her spiderlings to feast on her body thus giving her offspring the strength to spread themselves far and wide. Does a fox mother ever offer herself up to a predator to save her young, perhaps when benefits outweigh the loss? Do animals somehow calculate such actions?

We tend to assume that everything a wild animal does is controlled by pure instinct, by behaviors programmed deep within the DNA, but to what extent do animals make choices that will lead to their success or demise? Furthermore: Do animals understand (or sense) that they can be eaten at any time? Do they feel their own loss in the moments before their death, during the kill? I am an animal, after all, and I cannot fully grasp the fact that I, too, can be eaten right now as I sit in the middle of this wide gravel bar cradling my coffee mug to my cheek and scratching this pen across the paper.

6.

It rained all night—a soothing drizzle that made a pinging tune off the aluminum stovepipe and lulled me into a deep, moonless sleep. A new morning reveals a fresh layer of snow across the adjacent range and the hills over yonder. The sun emerges only briefly, glossing the foliage and casting dramatic shadows at an Arctic tilt. Now a heavier rain patters against the roof as the East Fork River churns and cuts into the land, as a delicate fog encircles us. It’s thirty-nine degrees according to the outside thermometer, but we intend to go for a hike, because, as someone tells us, There’s no bad weather, only bad gear.

Meandering across on the riverbed for hours on end, I consider the size and age of North America. I begin thinking about the passage of time and how some 70 million years, herds of duck-billed dinosaurs roamed these lands. The McKinley range was in its infancy then, a granite mass rising up millimeter by millimeter. Consider all the creatures that have lived and died in those years; all the species that have evolved; the seasons; the rotations of the earth; the revolutions around the sun; civilizations that have flourished and crumbled away—the Greeks, Romans, Mayans, Aztecs, Incas; queens and kings that have decomposed, become skeletons, and blown away in the wind.

On the one hand, how depressing! Clearly, we are but mere specks in time. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust. Here today, gone tomorrow. On the other hand, how exciting! What a miracle, to be alive at latitude 63.3333° North, longitude 150.5000° west. How eager this makes me to return to my family, my familiar humans, and to cherish these short moments. Isn’t the curse of being human this very awareness? The blessing of the bear is that he knows what his nose knows, which gives him a rawness of thought and feeling: to pounce on a squirrel must be an avid delight; to rub up against a tree; to gnaw on bark, to chomp a mouthful of berries. So with this awareness, I tell myself, I must be acutely aware of each breath; I must not let any of it slip by.

7.

What I have yet to realize is that a bear’s sense of smell is one hundred times greater than that of a human. Spaghetti sauce simmers on the cabin’s four-burner stove—Roma tomatoes and basil leaves bathed in olive oil, bubbling extra long until the juice turns thick and sweet. The cabin is more luxurious than I’d imagined, with a fully-equipped kitchen including a gas-powered refrigerator. I’d been prepared for ten days of “roughing it” and I’m feeling giddy at the thought of the easy days ahead that stretch before us in an arc of ten suns and nine moons. After a little bushwhacking and a long walk up Polychrome, nothing sounds better than a big bowl of pasta.

We’ve got the cabin door propped open and Dana is sitting at the table reading, when suddenly, she looks up, and says—“Bear!”

I glance out the door and gasp at the sight of a grizzly ambling up the path headed straight for us. He’s a gorgeous creature—all shoulder blades and claws, the tips of his fur, blonde and fluffed. “Oh my god,” we say. Dana grabs her camera and takes some pictures as it gets closer and closer, trailing after what must be a confusing and mindboggling aroma.

Quickly, we discuss whether we should yell, whether we should wave our arms, what the safety brochures say we should do. “Shouldn’t we at least close the door?” I say. Yes, we should now shut the door, we agree. But first, Dana decides to speak to the bear: “Go away. Go on, now,” she says. I am impressed at her natural ability to speak to a bear so firmly and so confidently, without alarm or anger.

Upon hearing Dana’s voice, the bear drops his head, turns around rather dejectedly, and then plops down onto his haunches with a groan. There he sits for a while having a good scratch. He glances back a few times toward the cabin, sniffing around half-heartedly. Then he paws at the ground a few times before standing up and making a wide, slow arc around the cabin, pushing his snout into the dirt, taking his sweet time. Finally he finds a good spot and hunkers down just beside the outhouse in plain view of the rear window. Because he moves so slowly and seems so sleepy, we are not afraid—though I do wonder what prevents him from tearing open that side window and eating whatever he damn well pleases. Instead, he lounges behind the cabin for a long time—an hour perhaps. With our steaming bowls of pasta, we get cozy in our chairs and watch this “nature show” through the back window, almost not believing what we are seeing. “It’s like Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom!” I say. “Can you believe this?” Dana keeps saying. “We’re the luckiest people on earth!” And then we ask ourselves, “How many people do we know who can look out their windows and see a grizzly bear just sitting there?” (Answer: Zero! Nobody!)

What I have yet to realize is that a bear’s sense of smell is one hundred times greater than that of a human. Spaghetti sauce simmers on the cabin’s four-burner stove—Roma tomatoes and basil leaves bathed in olive oil, bubbling extra long until the juice turns thick and sweet. The cabin is more luxurious than I’d imagined, with a fully-equipped kitchen including a gas-powered refrigerator. I’d been prepared for ten days of “roughing it” and I’m feeling giddy at the thought of the easy days ahead that stretch before us in an arc of ten suns and nine moons. After a little bushwhacking and a long walk up Polychrome, nothing sounds better than a big bowl of pasta.

We’ve got the cabin door propped open and Dana is sitting at the table reading, when suddenly, she looks up, and says—“Bear!”

I glance out the door and gasp at the sight of a grizzly ambling up the path headed straight for us. He’s a gorgeous creature—all shoulder blades and claws, the tips of his fur, blonde and fluffed. “Oh my god,” we say. Dana grabs her camera and takes some pictures as it gets closer and closer, trailing after what must be a confusing and mindboggling aroma.

Quickly, we discuss whether we should yell, whether we should wave our arms, what the safety brochures say we should do. “Shouldn’t we at least close the door?” I say. Yes, we should now shut the door, we agree. But first, Dana decides to speak to the bear: “Go away. Go on, now,” she says. I am impressed at her natural ability to speak to a bear so firmly and so confidently, without alarm or anger.

Upon hearing Dana’s voice, the bear drops his head, turns around rather dejectedly, and then plops down onto his haunches with a groan. There he sits for a while having a good scratch. He glances back a few times toward the cabin, sniffing around half-heartedly. Then he paws at the ground a few times before standing up and making a wide, slow arc around the cabin, pushing his snout into the dirt, taking his sweet time. Finally he finds a good spot and hunkers down just beside the outhouse in plain view of the rear window. Because he moves so slowly and seems so sleepy, we are not afraid—though I do wonder what prevents him from tearing open that side window and eating whatever he damn well pleases. Instead, he lounges behind the cabin for a long time—an hour perhaps. With our steaming bowls of pasta, we get cozy in our chairs and watch this “nature show” through the back window, almost not believing what we are seeing. “It’s like Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom!” I say. “Can you believe this?” Dana keeps saying. “We’re the luckiest people on earth!” And then we ask ourselves, “How many people do we know who can look out their windows and see a grizzly bear just sitting there?” (Answer: Zero! Nobody!)

8.

For most of the night, the sun

sits just below the horizon and casts a purplish light against everything.

Until 1 a.m. or so, there are no dark places, no shadows, really, just this

soothing low light that I believe I might get used to. On the road back from Wonder Lake, ten p.m.,

a moose sits off in the distance, legs folded delicately beneath his enormous

body, antlers resting on the ground. From a distance, the bowl and rise of this

enormous rack make him clearly visible across the flat tundra. Is it a burden

for him to carry these antlers? A pair of moose antlers can weight forty

pounds—maybe not such a burden for a thousand pound animal. Through the binoculars I observe that he is

not fully asleep, stirring slightly and half-aware, drowsing in this lowlight.

On this tundra of predator/prey, this lowlight seems a bonus. But with a

moose’s poor eyesight, light might not matter as much as the musky scent of a

wolf or the sound of a single, snapping twig.

In this low light, another moose wades in a kettle pond—no other creature his size visible for a mile in all directions. He’s graceful and lovely, this little dance he does of dipping his mouth into the water and lifting it up again, his antlers bowing and dipping with him; he in his own space, in this lavender light on that tundra that rolls out for miles and miles in all directions, framed by jagged snowy peaks and shale hills.

In the lowlight, two caribou bound lightly over shrubs, their fuzzy antlers like an elaborate candelabra—such artistry in nature! Their dark fur is rubbed off in patches, only remnants of their winter coat. Caribou move with light legs—not mechanically like deer or elk which seem less athletic in comparison to caribou, so clearly visible with their white-painted haunches. Do they stop grazing in the lowlight? Are their movements more subdued? To what extent can animals dim their awareness; can they ever just enjoy the view?

I believe a Dall sheep can enjoy the view. Even in near darkness, sheep can be viewed clearly through binoculars. Nestled in crags and crannies on velvety green hillsides at the top of North America, their snowy-white coats make them easy to spot in summer. They seem so insulated in their elevated paradise. In the lowlight, eleven sheep gently graze, the, one by one, lower themselves to their forelegs, still munching on grasses, their eyes closing part-way. Unlike bears who keep a tight circle round their cubs, lambs are allowed to wander off and frolic, bucking and prancing, at times a fair distance from the family. Adults lounge far apart from one another, legs folded beneath them. Sheep, however, wear their horns for a reason. I learn that during mating season, rams will fight with other males, rising up on their hind legs—almost flying!— charging each other in repeated head-on collisions. Thus far, I have been consumed with bears and wolves, but now I see these mountain-inhabitants with horns like rocks and brambles, coats melded from snow. They connect heaven and earth, poised over glacier valleys, steeled against violent winds. Even with hunters watching me through their scopes, even with wolves circling my heels, and even with those vicious arctic blasts, I would want to be a sheep, if given the option.

9.

Wilderness allows us the privilege of living “off the clock”—to rise at a pace similar to the animals that inhabit that space. In wilderness, we can mostly do as we please. I study the clouds and some raindrops fall onto my face; I dance around on an empty road and halt when I notice a gray jay staring at me. I stare back. Sitting on a rock, I study the heart-shaped leaves of an arctic birch—its veins like raised arms. Later I note the nod of a bluebell’s petals and admire the undulations of the river, and looking closer, the minerals and silt that swirl around inside of it, noting how that sparkly gray water grabs up debris and hurries it along.

Today I wander around outside the cabin, peering down at grasses and examining a fuchsia fireweed flower. I turn it round and round, noticing how the sticky pollen clings to the stamens as long delicate hairs unfurl around the petals, little invitations for bees. Suddenly I have a vivid memory: I see my first skateboard—a fiberglass beauty with red acrylic wheels, and there it floats, like a ghost hovering above this grassy hill. This leads to the memory of how I got this skateboard…another story, perhaps? So why did I suddenly envision my beloved skateboard while staring at this flower? Did its color jar my memory? What about the purple monkshood? The yellow of the tundra rose? Can memories and new ideas arise from these unfettered spaces? How rare are these days of uncharted time!

Wilderness, then, equals time. Open space allows us to consider our size as we stand alone on the tundra. Who are we, really, without all our things? Rather than diminish us, this feeling of smallness should liberate us, giving us faith in our silly ideas, showing us that “I” am as important and as unimportant as any other creature in the world, whether it be a marmot, an arctic squirrel, or the president. My equal importance and simultaneous lack of importance calms my worries, gives me courage to take creative risks, and to use my voice. Wilderness, especially Denali, is good medicine for all that ails us, as we city people continue to compete for space and for resources (both internal and external). Being in wilderness forces us to unplug from the chatter of information—no cell phones, no computers. All this uncontrolled chit-chat echoes until the noise makes fractals of our thoughts and memories.

I look outside the window. Rain and mist have settled, water ticking against the stovepipe. Suddenly I see another seemingly random image: my Brownie uniform—the one that I wore in the second grade. Why now? I can recall my chubby knees, my brown polyester knee socks, my orange snap-on tie, and how proud I felt wearing it. I can ignore the vision or I can follow it down the rabbit hole and see where it leads. Conclusion: These moments of tranquility—in this protected space—may truly be our last salvation, not just for inspiration, but to keep us pure of heart, healthy, connected with the past and able to envision the future. By studying this land and sketching a picture with words, we can also look inward. The trick is capturing those words before they disappear. Even here, words, like chickadees, flutter down and then arise in a second, all wings and chatter before they melt into the sky.

10.

Two pristine mountain bikes lean up against the side of the cabin and I’m itching to ride. The smooth 92-mile dirt road looks like a dream come true. Even with the occasional dust-up from a bus or pick-up truck, the road seems meant for bikes, for gravel churning under the tires, for standing up on the downhill.

Before our arrival Dan Irelan from Toklat Camp had kindly driven the bikes down to the cabin, along with helmets and a bike pump. I’d asked if we could borrow some bikes, and, voila! Here they are. Again, I feel like the luckiest person on earth. Tightening our helmets and adjusting our gears, we head up to Sable Pass, a restricted wildlife zone with signs posted forbidding hikers from wandering off-road. The land dips into a deep, lush valley where the rivers merge into streams, lots of them, and the tundra tilts and rises all around. With this surreal, painted landscape and gentle cloud-cover, I feel like I could ride for one-hundred miles without stopping. What I love about cycling is the feeling of moving through a place—of letting it wash over you like a stream. The chilly air cuts through you like a cold river, and it feels good to get sweaty. On a bike, there’s no telling what you’ll run into, and here, the odds of running head-on into a grizzly or a moose are pretty good, which makes riding, even slow uphill riding, especially thrilling.

We are becoming wildlife scouts, scanning the horizon for aberrations in color or shapes, peering high and low, near and far, across the horizon. Only minutes into our first ride, we spot a medium sized male grizzly. Of course I have no basis for calling him male, nor any real basis for deeming him “medium,” only that he looks pretty big but I’m sure he could be bigger, “he” doesn’t have cubs, and if he were any closer, I’d probably call him enormous.

I must try to explain the sensation of being on a bike—a familiar feeling—pedaling along, adjusting gears, hearing one’s own breath and the pleasant sound of dirt churning under the tires—and then seeing—from a bike—A GRIZZLY BEAR. We dismount quietly, scarcely breathing, beholding this creature. I Dana snaps some pictures and I try to discern which direction he’s heading and whether he’s noticed us. For the moment, he seems to be at a safe distance, but my instincts tell me to keep moving. Even though he looks to be several hundred feet away, without a fence or plexiglass window between us, that seems pretty darn close. To get to us, he would have to run down a hill, cross a narrow stream, climb back up a hill, and emerge onto the road. This distance would take most humans at least ten minutes, but I’ve been told that grizzlies can run pretty darn fast when they want to, even if only in short bursts, which would mean that this bear can get to us in a matter of seconds if he is so inclined. If he smells our veggie bologna sandwiches in our backpacks, he might just do that. This gets me thinking that humans must be pretty stinky to an animal with such a keen sense of smell—our natural odors must be quite gruesome, and then on top of that, all our lotions and powders and sprays must, to a bear’s sensitive nose, smell acrid and offensive.

One’s thoughts move at a hundred miles per hour when looking at a grizzly bear. But we can’t take our eyes off him: He’s gorgeous. Rambling in small arcs and semicircles, he paws the dirt with those comb-sharp claws, gnawing at leaves, yawning. Eat, eat, eat, seems to be the main purpose of the grizzly.

We hop back onto our bikes and keep riding. About another mile up the road, we spot a sow and her two cubs. We wobble and practically fall off our bikes when we see them. They, too, are foraging up against the hillside, but this family is much closer than the last one bear, and we know that cubs add a potentially dangerous dimension. If these cubs decide to come check us out, we’ll have a protective mama bear to contend with. Fortunately, the cubs don’t seem to notice us, although their mother sniffs pointedly in our direction, her nose wide and wet, her eyes trying hard to focus on our shapes. We decide to move, once again, not wanting to take any chances. Now with four bears between us and the cabin, it seems like a good day to keep on riding.

Once over Sable Pass, it’s mostly downhill all the way to the Sanctuary River, a distance of about twenty miles. With those bears behind us, more in front of us, and all around us, I feel terrified, joyous, and dare I say--alive! The landscape seems utterly surreal, as if painted by hand with impressionistic strokes of shale and wide swathes of green. We learn that the white flowers growing in abundance as far as our eyes can see are called “bear-flowers” and are the preferred food of the grizzly. Where there are bear-flowers, there are bears!

In this low light, another moose wades in a kettle pond—no other creature his size visible for a mile in all directions. He’s graceful and lovely, this little dance he does of dipping his mouth into the water and lifting it up again, his antlers bowing and dipping with him; he in his own space, in this lavender light on that tundra that rolls out for miles and miles in all directions, framed by jagged snowy peaks and shale hills.

In the lowlight, two caribou bound lightly over shrubs, their fuzzy antlers like an elaborate candelabra—such artistry in nature! Their dark fur is rubbed off in patches, only remnants of their winter coat. Caribou move with light legs—not mechanically like deer or elk which seem less athletic in comparison to caribou, so clearly visible with their white-painted haunches. Do they stop grazing in the lowlight? Are their movements more subdued? To what extent can animals dim their awareness; can they ever just enjoy the view?

I believe a Dall sheep can enjoy the view. Even in near darkness, sheep can be viewed clearly through binoculars. Nestled in crags and crannies on velvety green hillsides at the top of North America, their snowy-white coats make them easy to spot in summer. They seem so insulated in their elevated paradise. In the lowlight, eleven sheep gently graze, the, one by one, lower themselves to their forelegs, still munching on grasses, their eyes closing part-way. Unlike bears who keep a tight circle round their cubs, lambs are allowed to wander off and frolic, bucking and prancing, at times a fair distance from the family. Adults lounge far apart from one another, legs folded beneath them. Sheep, however, wear their horns for a reason. I learn that during mating season, rams will fight with other males, rising up on their hind legs—almost flying!— charging each other in repeated head-on collisions. Thus far, I have been consumed with bears and wolves, but now I see these mountain-inhabitants with horns like rocks and brambles, coats melded from snow. They connect heaven and earth, poised over glacier valleys, steeled against violent winds. Even with hunters watching me through their scopes, even with wolves circling my heels, and even with those vicious arctic blasts, I would want to be a sheep, if given the option.

9.

Wilderness allows us the privilege of living “off the clock”—to rise at a pace similar to the animals that inhabit that space. In wilderness, we can mostly do as we please. I study the clouds and some raindrops fall onto my face; I dance around on an empty road and halt when I notice a gray jay staring at me. I stare back. Sitting on a rock, I study the heart-shaped leaves of an arctic birch—its veins like raised arms. Later I note the nod of a bluebell’s petals and admire the undulations of the river, and looking closer, the minerals and silt that swirl around inside of it, noting how that sparkly gray water grabs up debris and hurries it along.

Today I wander around outside the cabin, peering down at grasses and examining a fuchsia fireweed flower. I turn it round and round, noticing how the sticky pollen clings to the stamens as long delicate hairs unfurl around the petals, little invitations for bees. Suddenly I have a vivid memory: I see my first skateboard—a fiberglass beauty with red acrylic wheels, and there it floats, like a ghost hovering above this grassy hill. This leads to the memory of how I got this skateboard…another story, perhaps? So why did I suddenly envision my beloved skateboard while staring at this flower? Did its color jar my memory? What about the purple monkshood? The yellow of the tundra rose? Can memories and new ideas arise from these unfettered spaces? How rare are these days of uncharted time!

Wilderness, then, equals time. Open space allows us to consider our size as we stand alone on the tundra. Who are we, really, without all our things? Rather than diminish us, this feeling of smallness should liberate us, giving us faith in our silly ideas, showing us that “I” am as important and as unimportant as any other creature in the world, whether it be a marmot, an arctic squirrel, or the president. My equal importance and simultaneous lack of importance calms my worries, gives me courage to take creative risks, and to use my voice. Wilderness, especially Denali, is good medicine for all that ails us, as we city people continue to compete for space and for resources (both internal and external). Being in wilderness forces us to unplug from the chatter of information—no cell phones, no computers. All this uncontrolled chit-chat echoes until the noise makes fractals of our thoughts and memories.

I look outside the window. Rain and mist have settled, water ticking against the stovepipe. Suddenly I see another seemingly random image: my Brownie uniform—the one that I wore in the second grade. Why now? I can recall my chubby knees, my brown polyester knee socks, my orange snap-on tie, and how proud I felt wearing it. I can ignore the vision or I can follow it down the rabbit hole and see where it leads. Conclusion: These moments of tranquility—in this protected space—may truly be our last salvation, not just for inspiration, but to keep us pure of heart, healthy, connected with the past and able to envision the future. By studying this land and sketching a picture with words, we can also look inward. The trick is capturing those words before they disappear. Even here, words, like chickadees, flutter down and then arise in a second, all wings and chatter before they melt into the sky.

10.

Two pristine mountain bikes lean up against the side of the cabin and I’m itching to ride. The smooth 92-mile dirt road looks like a dream come true. Even with the occasional dust-up from a bus or pick-up truck, the road seems meant for bikes, for gravel churning under the tires, for standing up on the downhill.

Before our arrival Dan Irelan from Toklat Camp had kindly driven the bikes down to the cabin, along with helmets and a bike pump. I’d asked if we could borrow some bikes, and, voila! Here they are. Again, I feel like the luckiest person on earth. Tightening our helmets and adjusting our gears, we head up to Sable Pass, a restricted wildlife zone with signs posted forbidding hikers from wandering off-road. The land dips into a deep, lush valley where the rivers merge into streams, lots of them, and the tundra tilts and rises all around. With this surreal, painted landscape and gentle cloud-cover, I feel like I could ride for one-hundred miles without stopping. What I love about cycling is the feeling of moving through a place—of letting it wash over you like a stream. The chilly air cuts through you like a cold river, and it feels good to get sweaty. On a bike, there’s no telling what you’ll run into, and here, the odds of running head-on into a grizzly or a moose are pretty good, which makes riding, even slow uphill riding, especially thrilling.

We are becoming wildlife scouts, scanning the horizon for aberrations in color or shapes, peering high and low, near and far, across the horizon. Only minutes into our first ride, we spot a medium sized male grizzly. Of course I have no basis for calling him male, nor any real basis for deeming him “medium,” only that he looks pretty big but I’m sure he could be bigger, “he” doesn’t have cubs, and if he were any closer, I’d probably call him enormous.

I must try to explain the sensation of being on a bike—a familiar feeling—pedaling along, adjusting gears, hearing one’s own breath and the pleasant sound of dirt churning under the tires—and then seeing—from a bike—A GRIZZLY BEAR. We dismount quietly, scarcely breathing, beholding this creature. I Dana snaps some pictures and I try to discern which direction he’s heading and whether he’s noticed us. For the moment, he seems to be at a safe distance, but my instincts tell me to keep moving. Even though he looks to be several hundred feet away, without a fence or plexiglass window between us, that seems pretty darn close. To get to us, he would have to run down a hill, cross a narrow stream, climb back up a hill, and emerge onto the road. This distance would take most humans at least ten minutes, but I’ve been told that grizzlies can run pretty darn fast when they want to, even if only in short bursts, which would mean that this bear can get to us in a matter of seconds if he is so inclined. If he smells our veggie bologna sandwiches in our backpacks, he might just do that. This gets me thinking that humans must be pretty stinky to an animal with such a keen sense of smell—our natural odors must be quite gruesome, and then on top of that, all our lotions and powders and sprays must, to a bear’s sensitive nose, smell acrid and offensive.

One’s thoughts move at a hundred miles per hour when looking at a grizzly bear. But we can’t take our eyes off him: He’s gorgeous. Rambling in small arcs and semicircles, he paws the dirt with those comb-sharp claws, gnawing at leaves, yawning. Eat, eat, eat, seems to be the main purpose of the grizzly.

We hop back onto our bikes and keep riding. About another mile up the road, we spot a sow and her two cubs. We wobble and practically fall off our bikes when we see them. They, too, are foraging up against the hillside, but this family is much closer than the last one bear, and we know that cubs add a potentially dangerous dimension. If these cubs decide to come check us out, we’ll have a protective mama bear to contend with. Fortunately, the cubs don’t seem to notice us, although their mother sniffs pointedly in our direction, her nose wide and wet, her eyes trying hard to focus on our shapes. We decide to move, once again, not wanting to take any chances. Now with four bears between us and the cabin, it seems like a good day to keep on riding.

Once over Sable Pass, it’s mostly downhill all the way to the Sanctuary River, a distance of about twenty miles. With those bears behind us, more in front of us, and all around us, I feel terrified, joyous, and dare I say--alive! The landscape seems utterly surreal, as if painted by hand with impressionistic strokes of shale and wide swathes of green. We learn that the white flowers growing in abundance as far as our eyes can see are called “bear-flowers” and are the preferred food of the grizzly. Where there are bear-flowers, there are bears!